Category: History Date: 2015-06-15

Life in a CCC Camp

This story was written by Carol Walker for the May-June 2014 edition of Down County Roads, a bimonthly magazine published by Southern Hills Publishing, Inc.

A Time to Remember

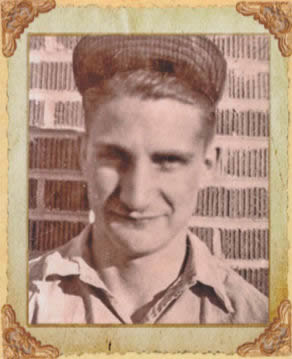

Jay Hendrickson can still remember it - CC7-266-973 - the serial number he was issued when he signed up for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a conservation and relief program spanning from 1933-1942, which was part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's (FDR's) New Deal.

Hendrickson has always believed it is an important part of American history and for that reason joined with others in a local chapter of the Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy, "a non-profit organization dedicated to research, preservation and education to promote a better understanding of the CCC and its continuing contribution to American life and culture."

The 1930s in the United States produced the "perfect storm." Stockholders lost more than $40 billion following the stock market crash of 1929 and 11,000 banks failed throughout the next decade. Without insurance on the bank deposits, many lost their life savings. The unemployment rate skyrocketed to more than 25 percent, most people had little money to purchase goods and high import taxes resulted in less trade with foreign countries. To top it off, in 1930 a severe drought in the Mississippi Valley, called the "Dust Bowl," forced many people to sell their farms.

When FDR came into office in 1933, people had endured that "storm" for three years and Roosevelt was primed to declare war on the Great Depression. To do this he needed an expansion of federal power to create the New Deal.

"I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis - broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe," said Roosevelt in his inaugural speech on March 4, 1933.

The president introduced Senate Bill 598 on March 27 and in four days it cleared both the Senate and House and was back on his desk for signature. The bill was the Emergency Work Act which provided for Emergency Conservation Work (ECW), later called the Civilian Conservation Corps. This program was designed to provide an income to millions of young men who would work in the preservation of forests, parks, lands and water all across the nation.

"The CCC should be remembered just like people remember the Great Depression because it is one of the great things that happened to this country. It was something that needed to be done at the time. I don't think that anything today could be put together as fast as the CCC," said Hendrickson.

In a couple weeks, by April 17, the first CCC camp opened at George Washington National Forest in Virginia, and by July 1, there were 1,300 camps across the United States with 275,000 single men between the ages of 17 and 25 working for $30 a month. A few years later, Hendrickson became one of the CCC enrollees at Camp Mystic in the Black Hills.

In 1929, his father moved the family from Huron to Pony Gulch in the Mystic area, where Hendrickson's dad became a carpenter and worked in the woods. Jay and his brother, Ray, attended the one-room schoolhouse in Mystic with about 35 other students where they learned the three R's. At that time he said there was a family living in almost every gulch in the area. Though times were tough, their family had the basics: wood for heat, water from the creek and wild game.

"We did not have running water or electricity, but we had a garden and a root cellar and things were much more laid back then. People shared with one another, so if one person got a deer, they would share it with others.

"The roads were very narrow and closed in the winter because there was no one to push the snow. But as kids, we ran the ridges, chased rabbits, skated on the ponds, fished and panned for gold. I helped my dad in the woods, too. We had parties and dances in people's houses. There would always be someone to play the violin. We built a church there, too. Once a month we would get to town," said Hendrickson.

One highlight for him during that time was piling onto a truck in the early morning hours with his Mystic classmates and traveling to the rim of the Stratobowl to watch the hot air balloon rise into the sky in 1935. Also, in1936 his family took a big trip to the South Dakota State Fair in Huron, where they stayed with cousins.

He said communication with the outside world came by way of the railroad. The train would come by twice a day on its way from Hill City to Deadwood. Bill Frink had a store at Mystic where they could get staples, but they could also order things from the Montgomery Ward catalog and have three-day delivery service by train from Denver.

"The depot agent in Mystic took meals with us and paid my mother $30 a month. My mother was a saint. She took care of us kids and never said anything about the rustic life we lived. She was a midwife and delivered 10 kids in the area. When someone was having a baby, she would be gone for two to three days at a time," said Hendrickson.

Hendrickson went through the ninth grade at the Mystic school and then had to decide what to do next. At 16 years old he was 160-170 lbs., six feet tall and had experience in the woods. With a little fudging of his age, he was able to enroll in the Mystic Camp as one of the Local Experienced Men (LEM) on June 1, 1937. He stayed there for two years.

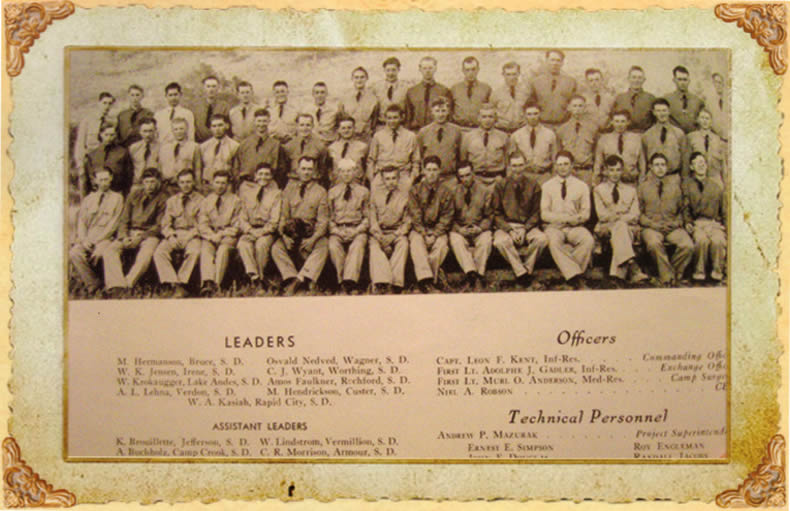

LEMs were hired from around the area to teach inexperienced crew members the skills needed to work in the woods. Crew leaders and assistant leaders earned a little more than $30 a month for supervising the men and the foremen were paid $140 a month to serve as on-the-job supervisors. Each camp had a superintendent and Army officers to take responsibility for day-to-day operations. Work projects were supervised by the Forest Service, Park Service, Soil Conservation Service, Bureau of Reclamation or the Bureau of Biological Survey. Hendrickson has positive memories of the time he spent at the Mystic Camp.

"We cut trees, planted trees, drove trucks and worked on roads. The CCC built many of the trails and logging roads through the Hills. We also fought forest fires," said Hendrickson.

Men who came to work in Black Hills camps were funneled through Fort Meade. In the early days of the CCC, there were sub-headquarters in Deadwood and Custer, but later all the processing of new enrollees was done at Fort Meade.

Eventually, age and marital status regulations were relaxed to allow World War I veterans and Native Americans who were in need to be involved with the CCC program. With all these men of varying ages, by the time the program ended, in South Dakota alone more than 28,000 men had spent time with the CCC.

"The CCC camp was run just like the military. We lived in barracks and wore uniforms. We would wake up every morning to revelry and there was work call and sick call. The food was just scrumptious. There were 10 barracks with 20 men in each one and there was a headquarters building and a garage to hold the trucks. We had an infirmary in every camp and there was an ambulance at about half the sites. I don't remember any one getting more than cuts and scrapes, except there was a guy who was working on a dump truck. The dump part felon him and he was killed," said Hendrickson.

Out of the $30 most men received each month, $25 was sent home to help the family or it was held in an account until the young man finished his term of enrollment which ran from six months to two years. Hendrickson said kids unable to read or write were taught to do so by an education officer. About 110,000 illiterate American men were taught to read and write during the CCC experience. They could also learn such skills as woodworking, auto mechanics and typing.

"We had every Wednesday and Saturday afternoons and all day Sunday off from work so we had time for recreation. There was baseball, basketball and boxing and a recreation room in the camp. The men ran track, went swimming, played checkers and chess and cribbage. We could also go to Hill City to watch a movie or go to a dance at the Legion Hall. The Legion Hall was the building that now has the museum (Black Hills Institute of Geological Research Museum). They always had a band," said Hendrickson.

The camp had a library for those who liked to read and an assortment of periodicals came in on a regular basis. Men could also attend the local church and there was a chaplain on hand to "infuse in them new hope and high character." He doesn't remember any trouble caused by the guys. They were just grateful to have work, according to Hendrickson.

He said in the Black Hills there were 17 main CCC camps and with the smaller side camps there were a total of 26 in the area. There were other South Dakota CCC camps in and around Pierre, Chamberlain, Belle Fourche, Camp Crook, Columbia, Martin,Wall, Alcester, Huron, Sand Lake, Lake Andes, Watertown, Presho, Belvidere, Canton, Lake Poinsett, Lake Norden and Interior. About 20 percent of the men enrolled in the CCC program came from outside the state. Some of the projects were done in conjunction with the Work Progress Administration (WPA), another federal relief program which began in 1935 and provided work for many people.

In the Black Hills the CCC built bridges, dams, roads, fire towers, cut trees and planted trees. They gathered pine cones, put up telephone lines, did landscaping and fought fires.

"Before the CCC camps there was only one lake in the Black Hills and that was Sylvan. Major Lake, Mitchell Lake and Newton were a result of dams built by the CCC men. They built Bluebell Lodge and the pigtail bridges and Mt. Coolidge tower and the Harney Peak tower," said Hendrickson.

Stanley Hawthorne, another Black Hills CCC alumnus, was a stone mason who worked on the steps to the Harney Peak tower. He entered the CCC in 1939 and was stationed at Camp Lightning Creek west of Custer and later at Sheridan.

"The CCC was a very positive experience. I learned the stone mason trade there and continued in it for almost 70 years," said Hawthorne, who recently turned 92 years old.

With camps all over the Black Hills, CCC men also built dams that created the following lakes: Center, Stockade and Legion in Custer State Park, Bismarck, Roubaix, Dalton (now Lakota Lake), Slate Creek and Lake of the Pines (now called Sheridan Lake). The dam for Sheridan Lake was the largest earth dam built by the CCC in South Dakota.

In Custer State Park the men also built the Peter Norbeck Visitor Center, the Wildlife Station on the Wildlife Loop Road and 17 cabins at Sylvan Lake. A CCC camp was located on the grounds that is now the Black Hills Playhouse. Buildings at Wind Cave National Park, Jewel Cave National Memorial and Badlands National Park were built by the CCC and the men were instrumental in establishing Canyon Lake Park and Wilson Park in Rapid City.

"Most all of the men I knew at the CCC camp have done well. Having employment at such a difficult time in our country gave them hope and it taught them a work ethic," said Hendrickson.

After his CCC experience, Hendrickson moved with his family to Rochford in 1939 where his father continued carpentry and his mother was the postmistress. Hendrickson went into military service and he believes his training with the CCC enabled him to climb the ranks quickly. Drafted into the Army in 1942 during World War II, he moved up to corporal in two weeks, to sergeant in another six weeks and shortly thereafter became staff sergeant. He went on to Officer Candidate School, became a second lieutenant and finally, by the time he finished his years in the Army, he was a captain. From 1946 to 1950, he was in the Reserves, being called up again for the Korean War from 1950-52.

Hendrickson's life in the Army was followed by employment in the grain and feed industry, building elevators, feed mills and dog food plants. In 1960 he established his own company, Grain States, Inc., retiring from it in 1990.

He has three children, two of them in Minnesota, and the third one will soon retire and also move to Minnesota. Hendrickson and Elaine, his wife of more than 50 years, have lived in Hill City since 2005. Prior to that, the Hendricksons spent several years in a house they built at Castleton, near Mystic, Jay's boyhood stomping grounds.

Hendrickson has been involved with the Lion's Club for many years and was instrumental in getting a new building constructed for the South Dakota Lion's Eye and Tissue Bank which provides about 500 corneas to people each year. Locally, the Lion's Club provides breakfast for bikers each year during the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, with the money going to scholarships and eyeglasses for those in need.

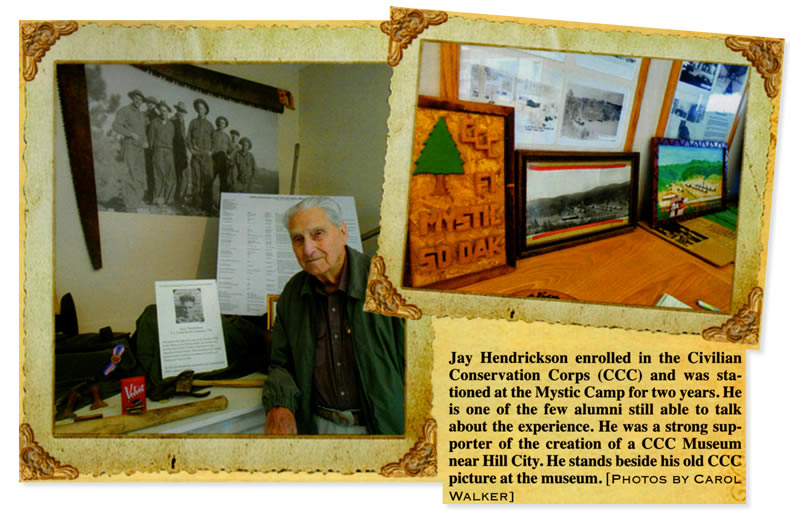

He has been president of the Hill City Senior Center, Rochford Chapel Board, Rochford Cemetery Board and received awards from the Lion's Club, the Catalyst Club and the Hill City Chamber. But, something he is extremely pleased to have been a part of is the establishment of the Hill City CCC Museum located in the Visitor Information Center (VIC) east of Hill City.

With a 2008 Outside of Deadwood Grant of $25,000, plans for the CCC museum began and the grand opening was in held in 2009. "Sarge" Melvin Hermanson, a South Dakota CCC enrollee, donated the money for the creation of a life-size bronze CCC Worker Statue that now stands on the grounds of the VIC. It is one of 61 other identical statues that are scattered across the United States honoring the three million men who participated in CCC programs during the nine years it was in existence.

Still with a keen mind, Hendrickson, age 93, is one of the few in the area who can still talk about the CCC days from personal experience. Growing up in the Hills during the Great Depression and spending two years in the Mystic CCC Camp shaped his life and today offer him rich memories of a time he believes should be remembered by all.

Hendrickson and Hawthorne, guys who lived the experience.

Jay Hendrickson can still remember it.